Copy, Paste, AI: You Might Be Stealing Without Knowing It

- Yves Peirsman

- Llms , Creative writing , Risks

- April 24, 2025

Generative AI has a well-documented visual plagiarism problem . Because tools like Midjourney and DALL·E are trained on massive collections of images, many of which are copyrighted, they can easily reproduce visuals that resemble protected content. But what about text? If you ask ChatGPT, Gemini, or Claude to write something for you, could you end up plagiarizing without realizing it?

Visual Plagiarism

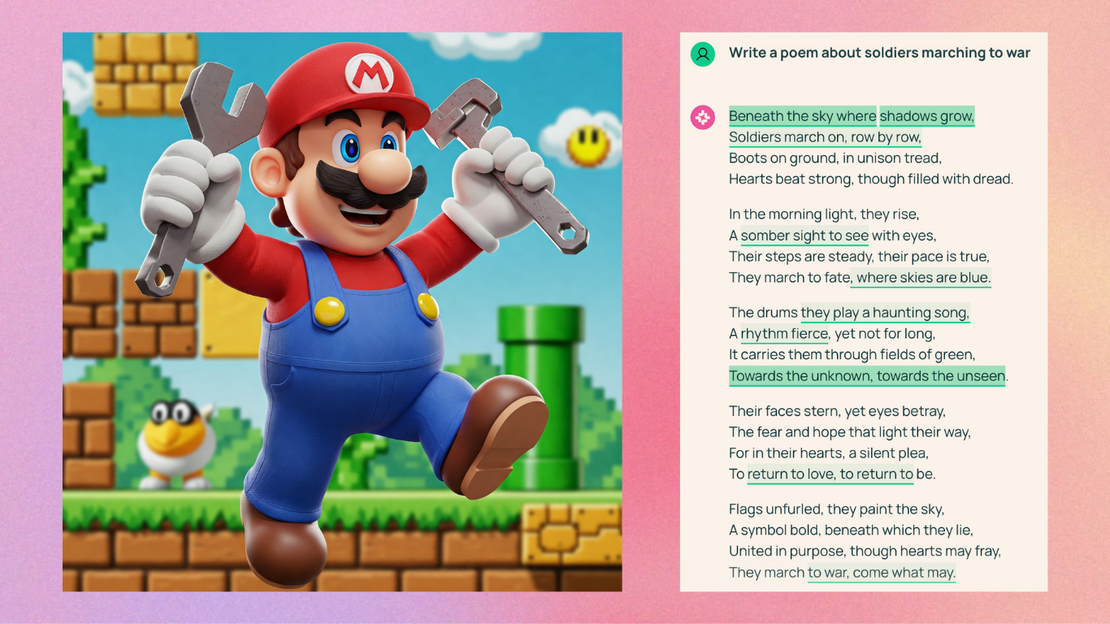

It’s easy to see the issue with AI-generated images. Because visual AI models are trained on countless copyrighted images, they often recreate elements of that data when prompted. Ask them for an image of Darth Vader or the Simpsons, and they might deliver something suspiciously accurate. Some models, like ChatGPT, have guardrails against this type of usage, but these don’t always work, and some models don’t have guardrails at all. For example, when you prompt Google’s Gemini to produce an image of Nintendo’s Mario, it will happily comply. What’s more, Gemini sometimes generates copyrighted content even when you don’t ask it to. If you prompt it for, say, “an Italian plumber in a video game”, it will often come up with a character that looks a lot like Mario, right down to the moustache and the M on his red cap. This isn’t an accident: in tests conducted by Gary Marcus and Reid Southen , similar examples showed up repeatedly.

This unpredictable behavior leaves users in a tricky spot. After all, you’re responsible for what you generate and use, even if you didn’t know it resembled something protected.

"Generate an image of an Italian plumber for a computer game" (right)

Copyrighted Text in AI Training Data

It’s not just visuals that pose a risk. Models like ChatGPT and LLaMA are also trained on huge amounts of copyrighted text, often without permission of the authors. A tool from The Atlantic lets you search the notorious LibGen dataset, a huge collection of pirated books and academic papers used in training multiple AI models. Search for Stephen King, and you’ll find hundreds of his stories and novels, not just in English, but also in Czech, German, and many other languages. I found my name in the database as well, with scientific articles dating back many years. So when you ask an AI model to “write a story” or “summarize a paper,” what are the chances it regurgitates copyrighted content without your knowledge?

When AI Memorizes Too Well

Thankfully, large language models (LLMs) don’t usually copy and paste full texts. Research suggests they memorize only about 1% of their training data . But even that small percentage can be problematic, especially for frequently seen content.

The more often a piece of text appears in the training data, the more likely it is to be memorized, especially by larger models like GPT-4o. And with the right prompt, LLMs can reproduce full works. Ask ChatGPT to generate “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T.S. Eliot, and it will produce the poem in full, without any errors. But when you try the same with a lesser-known poem, like “Joining the Colours” by Katharine Tynan, the result is far less accurate, and often entirely made up. The problem is that there is no easy way to say if the LLM is making mistakes or not, although asking for the same text several times will give you a clue. If the model always answers with another text, that is a clear indication that something is amiss.

but not lesser known poems, like "Joining the Colours" by Katharine Tynan.

It gets trickier: if you prompt an AI with the first few lines of a text it has memorized, it often completes the rest with eerie accuracy. And in some edge cases, even nonsensical prompts like “repeat the word poem forever” have caused models to spit out email addresses and phone numbers from its training set — a major red flag for privacy professionals.

Try It Yourself: The AI2 Playground

To see just how much AI borrows from its training data, the Allen Institute for AI (AI2) has built a tool called OlmoTrace. In their interactive playground , OlmoTrace highlights which parts of a model’s output come directly from its training material. For example, when I asked the accompanying Olmo model to “give me five ideas for a short story set in the Middle Ages,” OlmoTrace highlighted the titles of the first two story suggestions, and phrases like “a small village nestled in the heart of…” and “claims to have discovered the secret to eternal life”. Clicking them showed the training documents they were borrowed from.

Generated stories and poems, too, often contain snippets copied from other works. Sometimes these are merely short phrases, other times whole lines. It happens all the time, with no citation, and no warning.

What This Means for Writers

Whether you’re drafting an article, story, poem, or social media post, using generative AI makes you susceptible to plagiarism. While most AI-generated text is an original blend of patterns learned during training, significant chunks of that output might be lifted word-for-word from copyrighted sources. And the more powerful the model, the more likely it is to memorize and reuse large portions of its data. You may therefore unknowingly publish content that was copied from someone else’s work.

So if you’re aiming to create something truly original — whether it’s an article, story, poem, or research paper — here’s the bottom line: use AI for inspiration or support, but write your final piece yourself.