Why I don't use AI as a writer

- Yves Peirsman

- February 11, 2025

It has been following me ever since I published my first crime novel. Because I work in artificial intelligence, people ask me whether I use AI to write my books. I have to disappoint them, or reassure them, depending on who is asking. When I write stories, I prefer to stay far away from generative AI.

The Washing and the Cleaning

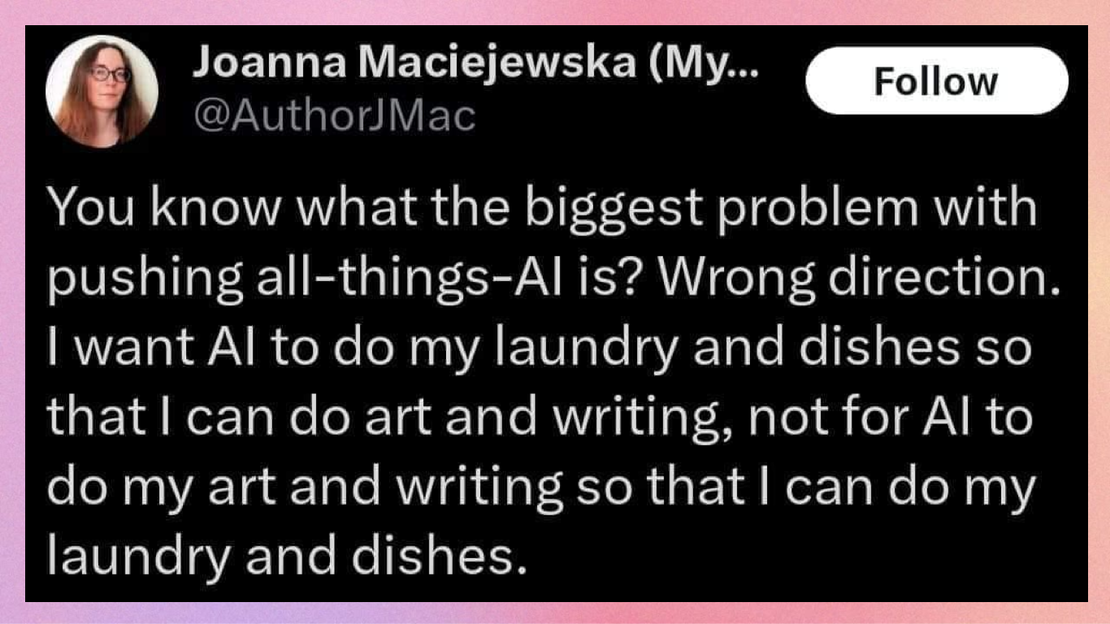

A while ago, writer Joanna Maciejewka went viral when she tweeted that she wanted AI to do her laundry and cleaning so she would have more time to write, rather than the other way around. It was a statement that split the audience into two camps. While many creatives agreed with her, there were also sneering comments that Maciejewka didn’t understand how AI works or that it was telling that she recoiled from AI when it took over her creative work but apparently had no problem with it threatening the jobs of cleaning staff.

There might be some truth to that. I sometimes catch myself mainly seeing AI as a threat when it encroaches on a field where I excel. But it’s also possible to read Maciejewka’s tweet simply as a personal choice: why would we let AI take over work that we actually enjoy doing? I completely understand why some people use software like Sudowrite or NovelCrafter to help them generate stories. I can see how writing a book with AI could be fun, especially for people who feel overwhelmed by the size of the task. But I personally enjoy coming up with a story structure, shuffling chapters around until they fit, and rewriting sentences over and over until they flow. So why would I let AI do that for me?

The average human

But that’s not the only reason. As a writer, you strive for a unique voice. You want to write a book that aligns as closely as possible with the vision in your mind, in a style that is entirely your own. The more you use AI, the harder that becomes. Because generative AI models are trained on such a vast array of texts, they often end up sounding like the average human. Andrej Karpathy, one of the big names in AI, put it this way on Twitter/X in November 2024: “Instead of the mysticism of ‘asking an AI,’ think of it more as ‘asking the average data labeler’ on the internet.”

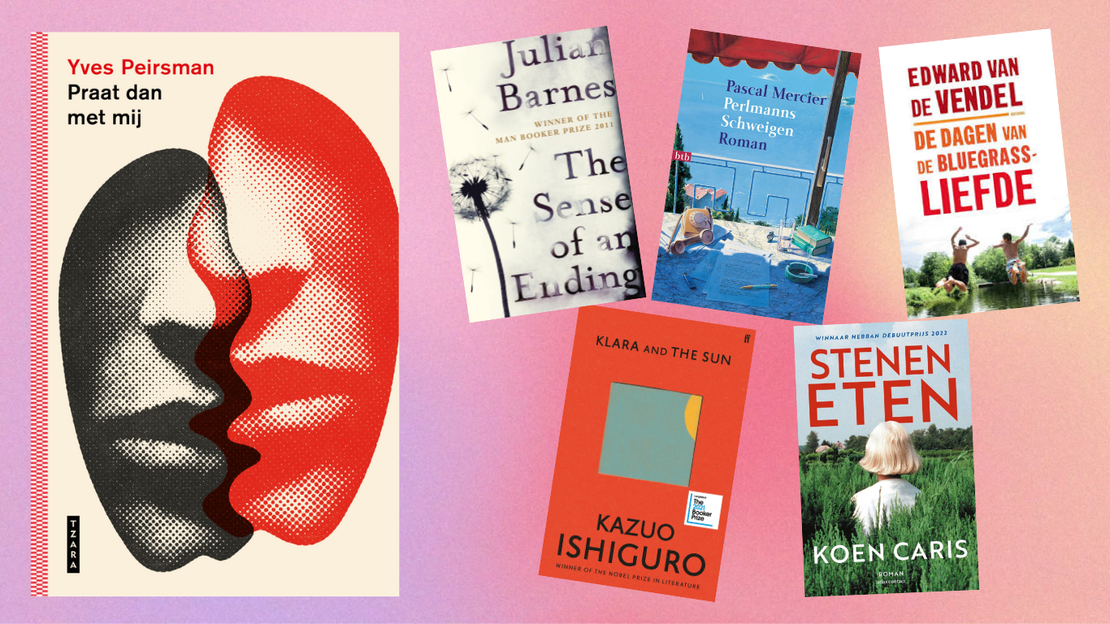

This is also a theme in Praat dan met mij (Talk to Me). My novel is about a man who wants to use AI to help his friend, who has a speech impediment, speak fluently again. By mapping brain activity and combining it with a language model like ChatGPT, he hopes to have a computer predict a patient’s next words. “But isn’t there a risk that your computer will steer your patients toward the average human?” someone asks him in the book.

“What do you mean?"

“Imagine…” He searched the pub for inspiration. “Your friend wants something to drink, for instance. He starts his sentence with I feel like a glass of. Your software will then fill in the most common drinks that follow those words, right?"

“Yes.”

“Those would be words like water, beer, or wine. But suppose your friend wants something else.” The bar next to us offered help. “Whisky. A specific brand, even. Talisker. He’s a connoisseur.”

“He can still type it out.”

“But isn’t there a risk that, out of laziness, he just selects beer? Because he dreads typing it out, and even more so, stumbling over the word himself?"

“I don’t think so,” I said. “The computer probably only needs the first two letters to suggest Talisker.”

“Tamdhu, Tamnavulin.”_

“Three then.”

“You underestimate how lazy people are.” It annoyed me how certain he was, as if he knew you, as if he was sure you wouldn’t make that small effort.

Karpathy added some caveats to his tweet. For certain tasks, including creative writing, companies do pay seasoned authors to produce texts for AI training. ChatGPT’s training data includes countless excellent novels. As a result, many generative AI models probably write better than the average human. But honestly, what writer wants to sound like the average of Margaret Atwoord, James Patterson and Suzanne Collins ? I certainly don’t.

The Greatest Art Heist Ever

That also brings us to the ethical issues surrounding AI. The training data of most generative AI models is packed with copyrighted texts, and their authors never gave permission for their work to be used for AI training. For that reason, some intellectuals consider the current AI revolution the greatest art heist of all time. The American Authors Guild called on tech giants like Facebook and Google in an open letter to stop these practices. Authors like John Grisham and Jonathan Franzen have even filed a lawsuit against OpenAI .

For the record: obviously I don’t find every application of AI problematic. In fields like medical science or transportation, AI can genuinely help us move forward. But in the creative sector, where prices are already under pressure and individuals struggle to defend themselves against multinationals, it’s a different story. A copywriter using ChatGPT for inspiration or a non-native speaker relying on Claude to make an English blog post flow more smoothly? Great! But a company replacing writers with machines? The internet rapidly filling up with so-called AI slop ? That’s something I’d rather not contribute to.

Author’s note

Of course, I’m not the only author who gets these kinds of questions. A year ago, writer Aline Sax shared a page from a book by Caimh McDonnell with me. In an author’s note, McDonnell assured the reader that he had written his book entirely by himself. He describes more beautifully than I ever could why he is so hesitant about AI: “Creativity isn’t about imitating others to get it right, it’s about getting it wrong in the right way.” Writing isn’t about efficiency. It’s about exploring ideas, questioning things, and discovering yourself through a story. Every writer has to decide for themselves how much AI they allow into their work — as an inspiration, a co-author, an editor, or a proofreader. But when I write my stories, I do none of these things. This is where I draw the line.